By Leigh Swigart [Photo credit PNAS]

The COVID-19 era has shone a spotlight on the challenges experienced by many multilingual societies in effectively communicating critical health information, particularly to members of vulnerable and minority populations. These difficulties have been well documented, for example, in OneSmallWindow for the UK, and in a variety of settings across the globe in “Language Diversity in a Time of Crisis”, a series published by the research platform Language on the Move.

The advocacy organization Cultural Survival recognized early in the pandemic that Indigenous peoples were especially vulnerable to COVID-19 and they have mounted a coordinated response to mitigate its impacts, including through the translation and communication of COVID-related information across diverse language communities. More recently, the UN Human Rights Council has confirmed that Indigenous populations have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 “as the pandemic had exposed and exacerbated pre-existing structural inequalities and systemic racism.”

Another kind of language challenge has also arisen in Indigenous communities across the world during the pandemic era – the unanticipated and rapid death of elderly speakers of endangered languages, and the associated loss of the unique concepts, sensibilities, and environmental knowledge that they embodied. This phenomenon has been documented in relation to a number of Native American communities – including the Yuchi, Ichishkíin and Cherokee – where the death of elders with the deepest knowledge of their languages can be likened to “losing an entire library.” The loss of languages may also interfere with community members’ ability to interact “with sacred foods and the natural world”. A powerful interactive CNN piece, Losing Languages, Losing Worlds, illustrates the connection between languages and worldviews – and in particular, understandings of the environment – by focusing on the endangered North American language, Potawatomi.

Valuable perspectives on the natural world are found not only in North America but in Indigenous communities across the globe. In an article about the resurgence of Maori songs in contemporary New Zealand, The New York Times reports that Maori is a very metaphorical language associated with a worldview that is more connected with nature, and that it doesn’t necessarily follow Western assumptions. New Zealander musician Lorde (who is white and whose singing in Maori has come under criticism), says she has been inspired by the Maori concept of “kaitiakitanga,” meaning “guardianship or caregiving for the sky, sea and land.”

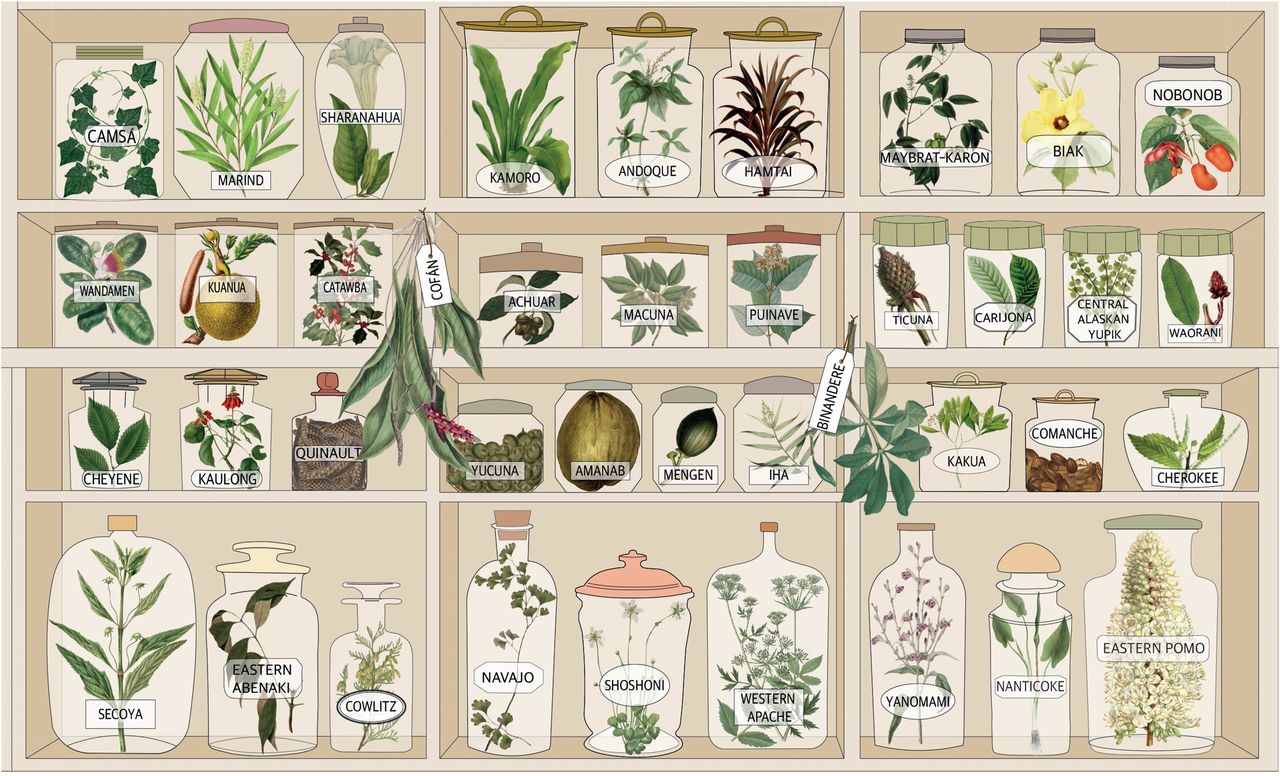

Placing value on responsible stewardship of the environment may also be accompanied by special insight into the properties of one’s natural world. Andrew Warner recently wrote of the botanical impacts of language decline in Language Magazine, noting that Indigenous language extinction triggers the loss of unique medicinal knowledge. He cites a 2021 research article by Swiss researchers in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), carried out in North America, the Amazon and Papua New Guinea. “[T]he researchers concluded that a significant degree of knowledge surrounding medicinal plants is encoded in just one language alone… While the plants themselves are not typically endangered, the languages that encode information and knowledge about their uses are endangered, meaning that these plants and their medicinal properties will be rendered useless.” A 2019 PNAS research article similarly notes that “cultural heritage is as important as plants for preserving indigenous knowledge both locally and regionally… Unlike the burning of the Library of Alexandria, however, the knowledge acquired by nonliterate societies may vanish in silence.”

In conclusion, the death of Indigenous languages – accelerated by that of their most knowledgeable speakers – may mean losing unique perspectives on the environment and valuable remedies that can be derived from the natural world. As societies across the globe struggle to meet the challenge of an illness unknown to us until recently, we should consider how best to protect and promote systems of speaking, perceiving and knowing that can benefit all of humanity in the future.