This month’s Spotlight was contributed by Dr. Shawna Shapiro (Middlebury College)

Over the past several years, many higher education institutions have begun to devote more attention to issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ)—particularly as it pertains to the experiences of students of color and other groups that been historically marginalized. Although “diversity” has been a focal point for educational discourse for decades, there is a growing consensus that simply “counting people” is not the same as “making sure each person counts”—i.e., ensuring that every student (and employee) feels seen, valued, and supported in achieving their goals (Lesko, 2019; Tienda, 2019).

Another piece that often gets lost in DEIJ work is the role of linguistic and cultural differences as axes of inequity. Students who speak a language variety other than standardized English at home or with friends may be told, for example, that their typical ways of communicating are simply “not appropriate” for school (Flores & Rosa, 2015; Matsuda, 2006). They may be labeled as less intelligent or capable, based on their level of conformity with white, native speaker standards (Charity Hudley et al., 2022; Clements & Petray, 2021; Schreiber et al., 2021; more on “linguistic profiling” in this 2022 blog post, also with LCJH). Culturally, students who were raised to take the needs and expectations of their families and communities into account when making educational decisions are sometimes baffled or alienated by the hyper-focus on individualism at U.S. colleges and universities (e.g., Shapiro, Farrelly, & Tomaš, 2023). Many of our academic policies and practices are based around capitalist cultural constructs such as “intellectual property” and academic “ranking,” which prioritize competition over collaboration.

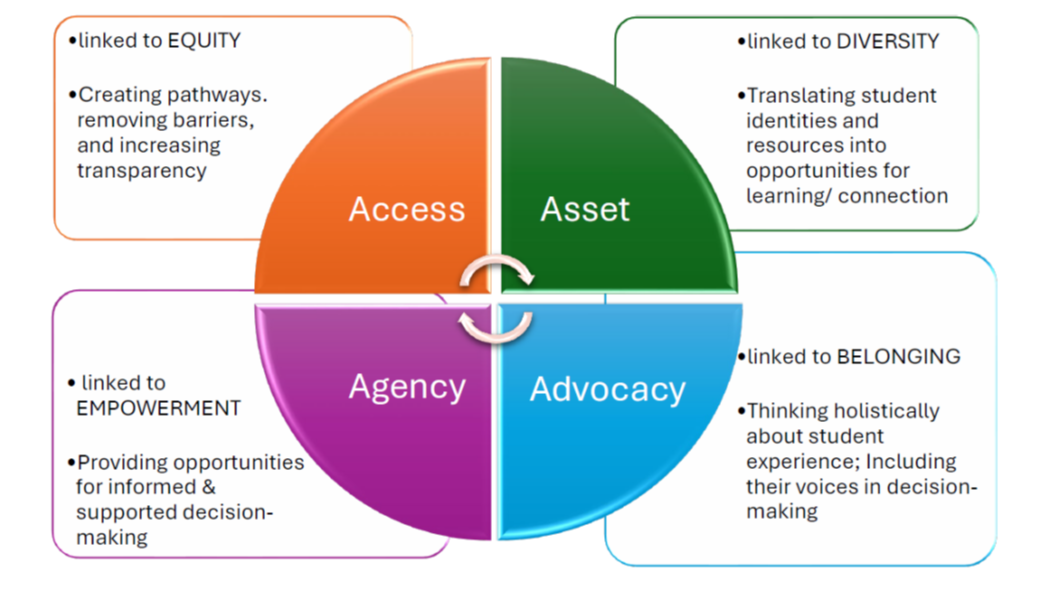

If we are committed to ensuring that students from diverse racial, linguistic, cultural backgrounds are treated as contributors to educational excellence, rather than as deficient or unwelcome, we need tools that can help us articulate our vision and align our policies and actions with that vision. This article presents one such tool: a framework for linguistic and cultural inclusion centered around four core values: Access, Asset, Agency, and Advocacy. These values work together, like the legs of a stool, to form a conceptual foundation from which we can build structures, policies, and practices that increase belonging and success for students from all linguistic and cultural backgrounds. This tool is informed by insights from critical linguistics, multicultural education, and social justice pedagogy, including earlier work from my frequent collaborator Zuzana Tomaš (see also Tomaš & Shapiro, 2021).

Below, I define each of the four values. linking them to other DEIJ concepts. I then provide reflection questions to help other practitioners reflect on the relevance of each value to their own work, along with a few examples of what a commitment to that value might look like in practice. I provide a graphic at the end that captures the ‘gist’ of the four values. I hope that this resource helps practitioners in higher education—and perhaps other fields as well—to translate their commitment to linguistic and cultural inclusion from theory into daily practice.

Value #1: Access

The value of “access” involves creating pathways and removing barriers to student engagement and success. This value is closely linked to equity: Equity is different from equal-ness: Rather than trying to treat each student in the exact same way, we need to consider policies, practices, and resources that are particularly helpful to the students most likely to struggle (see American University for more on this). The value of access encourages us to be explicit with students–and with ourselves–about our assumptions and expectations (Shapiro, Farrelly, & Tomaš. 2023). Access is also often linked to universal design for learning or inclusive design. The idea here is that as we design educational opportunities and resources, we want to be expansive in our thinking about who the intended audience is and how they might engage with our offerings.

Some of the questions we might reflect on, informed by the value of access, are:

- What norms and expectations are most crucial to student success in our program/department/institution? How can we be more transparent with students about those norms and expectations?

- What barriers prevent students from being successful in our courses/programming, and what supports or policies might we put in place or change in order to lessen those barriers?

- What kinds of feedback do we collect (or could we collect) to understand student experiences of struggle and success with academic, co-curricular, and extracurricular engagement?

Some examples of access-oriented work in higher education include:

- Offering guidelines and professional development opportunities for faculty and staff, focused on making expectations explicit, removing barriers to engagement, and providing equitable support

- Making important information available in multiple formats (written text, video/audio, graphic/visual) and, where possible, in multiple languages

- Providing a variety of modes for students to receive tutoring, advising, mentoring, or other support—e.g., online and in-person, synchronous and asynchronous, individual and group formats.

Value #2: Asset

The value of “asset” is closely linked to diversity, which has been a major focus for U.S. colleges and universities for many years, as noted earlier. However, the concept of asset invites us to think more deeply about what we do with diversity: How do we translate the various identities, experiences, and resources students bring with them into opportunities for learning and connection across the student body? (e.g., Losey & Shuck, 2022; e.g., Shapiro, Farrelly, & Tomaš, 2023). Some of the questions we might ask, informed by the value of asset, are:

- What do we know about incoming students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds, in addition to their goals, experiences, and interests?

- How are we preparing staff and faculty to recognize and build on students’ linguistic and cultural knowledge and skills?

- Where might we be more attuned to how linguistic and cultural factors shape students’ sense of welcome and belonging at our institutions?

Some examples of asset-oriented work in higher education include:

- Gathering more in-depth data on the linguistic and cultural backgrounds of students and faculty/staff through linguistic identity surveys (e.g., Lorimer Leonard et al., 2023), and using that data to design learning opportunities that build on these assets

- Providing academic and co-curricular offerings that allow students to develop interracial, intercultural, multilingual and global competencies—and not just in world language departments or ethnic studies programs (e.g. the Consortium on Cultures and Languages Across the Curriculum, including at Skidmore College; the JusTalks program at Middlebury College)

- Creating opportunities for students to draw on their linguistic and cultural backgrounds, such as multilingual writing for public audiences (e.g., GMU’s Valuing Written Accents program), multilingual tutoring or other academic support (e.g., Dickinson’s Multilingual Writing Center; see also Bugingo & Zatryb, 2024) and cross-cultural community engagement (e.g., Middlebury’s “Language in Motion” program).

Value #3: Agency

Agency refers to an individual’s ability to take desirable action within a given set of constraints or structures (e.g., Shapiro et al., 2016). In higher education, students may have opportunities to exert their agency in making decisions about what they study, how they demonstrate their learning, and what co-curricular and extracurricular activities they engage in, among other things. Cultivating student agency requires not just options for students to choose from, but also the information, skills, and guidance necessary to make informed choices and to evaluate the impact of those choices. Agency is closely linked to the concept of empowerment, which contributes to students’ sense of belonging.

Questions we might ask informed by the value of agency include:

- What choices do students have about courses, curricula, and programs of study? What resources and guidance do we provide to help students make those decisions confidently?

- Where might we build in more opportunities for students to make informed decisions, from the micro level (e.g., modes of communication, options for course assignments) to the macro level (degree options and pathways; co-curricular and extracurricular opportunities)?

- Where do we (or could we) provide opportunities for students to reflect more deeply on the impact of their educational decision-making and to consider alternate approaches and pathways?

Some examples of agency-oriented institutional policies and practices include:

- Using “guided” or “informed” self-placement for enrollments into developmental English and/or math courses, rather than automatically assigning students based on test scores or high school grades (see Morton’s (2022) review of research on this model)

- Creating opportunities for community-based learning and/or capstone projects within the curriculum (These are two of the “high impact practices” advocated by the American Association of Colleges & Universities)

- Collecting ongoing feedback about the most valuable learning experiences students are having within and beyond the academic curriculum (see, for example, the multi-institution Meaningful Writing Project)

Value #4: Advocacy

While the previous three values focus primarily on our direct work with students, the value of advocacy urges us to consider how to invite student perspectives into programmatic and institutional decision-making. To promote sense of belonging and justice within linguistically and culturally diverse institutions, we need holistic and sustained data on student experiences, as well as opportunities for a range of individuals and offices to collaborate in the creation and implementation of policies and actions. The value of advocacy also urges us to highlight the threads of “language” and “culture” within DEIJ conversations and initiatives, since, as was touched on earlier, these threads often get lost (Charity-Hudley et al., 2022; Schreiber et al., 2021; Shapiro et al., 2023).

Some of the questions that might guide our advocacy work include:

- What data/feedback does our institution collect on various aspects of student experience? (e.g., annual surveys, course evaluation forms, other institutional assessments). What can we learn from that data about student successes and struggles? What additional information do we need to fill in gaps in our current understanding?

- Where have I/we observed persistent exclusion, inequity, or marginalization among students? What people and entities might have the authority to address these concerns? How can we empower and incentivize change among those people and entities?

- Where might we make more space for student voice and input across the institution? (e.g., student representation on committees, focus groups or other share sessions that center student perspectives)

Some examples of advocacy-oriented practices include:

- Encouraging, supporting, and incentivizing curricular revision among faculty, in order to faculty to broaden the linguistic, cultural, and geographic representation in their course materials and assignments.

- Developing academic policies that promote multilingualism and intercultural competence (e.g., requiring global and/or cross-cultural learning as part of institution-wide learning goals, offering language credit to students who demonstrate proficiency in a language other than English, recruiting academic tutors from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds)

- Inviting representatives from a broader range of student-facing offices to join DEI committees or initiatives, including international student offices, study abroad, writing programs, and careers and internships.

I hope that this article offers a useful framework for thinking about linguistic and cultural inclusion in your own work, whatever role(s) you serve in at your institution. The questions and examples provided here are just a starting point: A campus or organization could productively engage with this framework by crafting its own reflection questions and identifying examples (and counter-examples) from their policies and practices. This framework may be useful as well to professionals in other fields outside of higher education. Below is a graphic that can serve as a quick reference for remembering the four values we have discussed:

References and Further Reading

Bugingo, M., & Zatryb, R. Aquí Se Habla Deutsch, Française, Kinyarwanda y ကညီ: Making multilingualism audible in writing centers. The Peer Review 8(1). Available HERE

Charity Hudley, A., Mallinson, C., & Bucholtz, M. (2022). Talking college: Making space for Black language practices in higher education. Teachers College Press.

Clements, G., & Petray, M. J. (2021). Linguistic discrimination in US higher education. Routledge.

Flores, N., & Rosa, J. (2015). Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 149-171.

Lesko, J. (2019, September 23). The illusion of inclusion. [blog post]. Inclusion in Action Elearning. Available HERE.

Lorimer Leonard, R., Bruce, S., & Vinyard, D. (2023). Finding complexity in language identity surveys. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 22(2), 167-180.

Losey, K. M., & Shuck, G. (Eds). (2022). Plurilingual pedagogies for multilingual writing classrooms. Routledge.

Matsuda, P. K. (2006). The myth of linguistic homogeneity in US college composition. College English, 68(6), 637-651.

Morton, T. (June 2022). Reviewing the research on informed self-placement: Practices, justifications, outcomes, and limitations. [Research brief for the Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/CAPR_Lit_Review_1.7.pdf

Schreiber, B. R., Lee, E., Johnson, J. T., & Fahim, N. (Eds.). (2021). Linguistic justice on campus: Pedagogy and advocacy for multilingual students (Vol. 96). Multilingual Matters.

Shapiro, S., Cox, M., Shuck, G., & Simnitt, E. (2016). Teaching for agency: From appreciating linguistic diversity to empowering student writers. Composition Studies, 44(1), 31-52.

Shapiro, S., Farrelly, R., & Tomaš, Z. (2023). Fostering international student success in higher education. (2nd edition). TESOL Press/NAFSA.

Tienda, M. (2013). Diversity≠ inclusion: Promoting integration in higher education. Educational Researcher, 42(9), 467-475.

Tomaš, Z., & Shapiro, S. (2021). From crisis to opportunity: Turning questions about

“plagiarism” into conversations about linguistically responsive pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 55(4).

Other Relevant Online Resources

- The Statement on Language, Power, and Action (revised in 2022) from the Conference for College Composition and Communication, which includes core concepts about language and power, as well as “Recommendations for Praxis” at the level of writing classroom/curriculum, program, and institution.

- “10 Ways to Tackle Linguistic Bias in our Classrooms” (January 2021), from Inside Higher Ed, which includes suggestions that can be employed by faculty across disciplines.

- Demand for Black Linguistic Justice (July 2020) from the Conference for College Composition and Communication, focused on linguistic inclusion and agency for Black Language users.

- CLA Collective– Dr. Shapiro’s resource page for Critical Language Awareness pedagogy.

Shapiro, Farrelly, & Tomaš (2023) Fostering International Student Success in Higher Education. Available via TESOL, NAFSA, and Amazon, among others

(Companion website can be found at www.tesol.org/FISS)